Current Status and Challenges of the Japanese Economy

Yoshikawa Hiroshi, President, Rissho University

The Current COVID-19 Pandemic

Yoshikawa Hiroshi, President of Rissho University

The current state of the Japanese economy is at a postwar low point not just in Japan but across the world due to the spread of COVID-19 since early 2020, and this is our biggest problem at present.

On top of the normal influenza in winter, the spread of a third wave is feared in Japan.

What will happen to the Japanese economy amid that? The second quarter of April through June, 2020 showed -28.1 points (second preliminary estimate), the lowest in the postwar period. This was a dramatic drop even in comparison to the Lehman Shock. A major factor here is the drop in consumption. About 60% of Japan’s GDP of some 500 trillion yen is consumption. At the very heart of the economy lies household and personal consumption. Consumption is stable compared to capital investments and exports. This is because our lives cannot fluctuate from day to day or month to month.

However, this time, consumption has been extinguished intentionally as a measure against COVID-19. Looking at different types of consumption, people refraining from going outside has hit the service sector more directly than the consumption of things. Consumption related to eating out and sightseeing dropped drastically. I suspect this is a rather unique pattern in world economic history since the start of the nineteenth century.

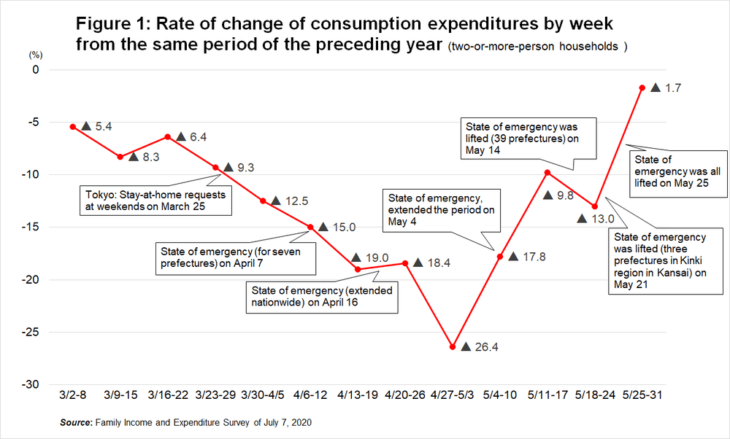

In July 2020, the Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (Statistics Bureau) published the Family Income and Expenditure Survey for May, which included statistics on consumption expenditures by week as a special appendix to the survey. The statistics are normally by month, so this is an interesting appendix for the COVID-19 pandemic. Looking at the consumption trends by week around the time of the first wave of COVID-19, consumption started a monotonous descent in March, reaching -26.4 points after the declaration of the state of emergency (April 7, 2020) and at the bottom of the first wave, meaning between April 27 and May 3. It stayed negative after that and kept dropping until May 31.

Figure 1 shows the rate of change compared to the previous week with the fall rapidly returning to zero after the end of the so-called Golden Week holidays (from the end of April to early May). The level seems to be bottoming out. The weekly consumption statistics show that the fall around Golden Week was due to policy-related, intentional consumption cutting. Around that time, Governor Koike Yuriko was calling on Tokyo residents to stay at home almost on a daily basis.

Abenomics, Evaluated after Seven Years and Eight Months

After that, Prime Minister Abe Shinzo retired (September 16, 2020), thus creating the Suga Yoshihide administration. This spelt the end of Abenomics after seven years and eight months and the media started debating how to evaluate that period. A variety of opinion polls were conducted after Prime Minister Abe announced his resignation (August 28, 2020).

The first to bring the topic up was the newspaper Asahi shimbun, with about 75% responding that they evaluated it positively. The opinion polls of other major newspapers likewise had about 75% “positively evaluating” it “greatly” or “somewhat.” However, these evaluations do not match the real figures.

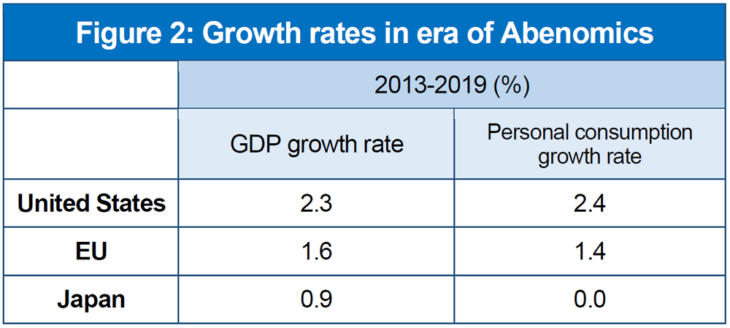

Let us compare the growth rate of the Abenomics period with those of other advanced countries. We can look at the period until the fourth quarter of 2019. This is a once-in-a-century extraordinary situation, so it makes no sense to compare the numbers after entering 2020. As such, we will limit the comparison to the seven years or so of Abenomics that cover the calendar year period from 2013 through 2019. Figure 2 shows a comparison of real growth rate for GDP and personal consumption between the United States, the EU and Japan.

The United States is clearly very stable. People have been saying that the EU has been doing extremely poorly. It is true that employment has been extremely bad, but both growth rates exceeded 1%. Compared to other developed countries, Japan is clearly doing poorly. If we take these figures into account when looking at the opinion poll results, it seems that the Japanese people do not understand Japan’s position in international trends.

The United States is clearly very stable. People have been saying that the EU has been doing extremely poorly. It is true that employment has been extremely bad, but both growth rates exceeded 1%. Compared to other developed countries, Japan is clearly doing poorly. If we take these figures into account when looking at the opinion poll results, it seems that the Japanese people do not understand Japan’s position in international trends.

At a time when developed countries are said to suffer from long-term stagnation globally, the personal consumption growth rate is growing at 2.4% for the United States and 1.4% for the EU. There is no getting around the fact that Japan’s personal consumption growth rate of 0% over seven years is extremely poor.

To begin with, who actually created this word “Abenomics”? This word, which appears to have become established historically, has some kind of meaningful substance and we are somehow captivated by it. Yet this is not particularly healthy. What were the seven years and eight months of the Abe administration and especially the seven years of economic policies before the coronavirus? How many results were produced or not produced? This is something we can talk about fully well even without using the word Abenomics.

Firstly, the growth really is not something to be praised. I have already said that. Yet when it comes to employment, some say the unemployment rate became extremely low and the active job openings-to-applicants ratio increased. This is a fact too and revealed by the numbers. Yet we also must not forget that the underlying trend has been a shrinking productive population and an economy of insufficient manpower.

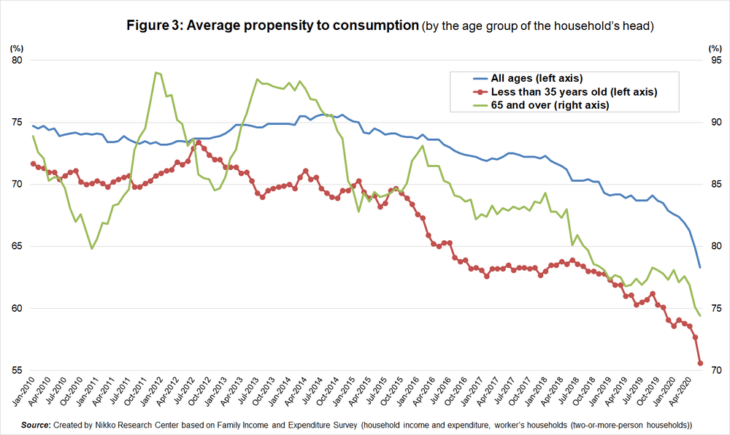

In the case of Japan, propensity to consumption has collapsed entirely. To state it roughly, the big issue of the Japanese economy is the utter failure of consumption, which makes up more than 60% of GDP. There are two reasons. One is that wages do not rise, and incomes do not increase. The other is that the propensity to consumption is going down across generations, which means that people are saving. It is thought that the cause is this anxiety for the future in a broad sense.

The young working generation also faces the issue of having difficulties finding regular employment. I believe the issue behind the anxiety for the future, across generations, is anxiety for the future of social security. There are other worries too, but I think social security is a big one.

I also want us to look at the composite index (CI). Business conditions were at their lowest in November 2012 and then entered a period of expansion. They were at their highest in October 2018 and then the economy entered a recession in 2019.

The CI is determined extremely mechanically. Economists in the private sector had been saying that it would peak in the fall of 2018 so that is not a surprise in itself, but it appears that this result was not so welcomed by the government and the Bank of Japan (BoJ). That is because the government and the BoJ had judged that the economy would basically continue to recover also in 2019. The CI uses figures compiled by the Cabinet Office every month, but the official market judgments of the government itself are made in the Monthly Economic Report. There it said that business conditions would basically keep improving in 2019 too. COVID-19 appeared at the end, so I guess they wanted a convincing story that blames everything on the virus.

Future Anxiety for Growing Disparities and Social Security

Next, we have the medium- to long-term. A major issue of the Japanese economy and society is growing disparities. Especially in the case of Japan, population aging is a big driver of growing disparities.

Japan is a front runner of population aging. If you gather one million people in their 20s, there will be relatively little variation in income, assets and health. By contrast, if you gather one million people aged 70 years or older and look at those same three factors, there will be much more variation than for those in their 20s. As population aging increases the variation ratio inside the group, it is only natural that variation for society overall also increases. This logic has had powerful effects so far and will continue to operate.

Public assistance is the final safety net. It is part of the social security system. The majority of benefitting households are those of senior citizens. In particular, it is women, or to put it simply old women living by themselves, who are the most common. Poverty is related to population aging.

Aside from the growing disparities related to population aging, one cause of long-term stagnation of the economy is disparity between regular and non-regular workers. At the time of the bubble economy, Japan supposedly had a non-regular workers’ ratio of one out of six. As a percentage, that is 16-17%, and recently it has grown to almost 40%. The economic benefits of a non-regular worker are simply worse than those of a regular worker.

By the way, the marriage rate of non-regular workers is lower than that of regular workers. In the statistics, there is something called “proportion currently married.” This is lower for non-regular workers than for regular workers.

In the case of Japan, unlike countries like France and Sweden, the legal position of children out of official marriage is extremely weak. As such, not marrying is basically a straight path to not having children.

All of Japan is saying that the declining birthrate is a problem for society as a whole and efforts are being made to somehow increase the total fertility rate. At the same time, Japan’s reality is that non-regular workers, whose proportion currently married is markedly low, have gone from 16% to 40%. Although each part may have its logic, the overall picture is incoherent.

Before moving on from the growing disparities, I want to point out that COVID-19 is also causing the same. The problem is that non-regular workers are the first to not have their contracts renewed.

Disparities are a global problem. The French economist Thomas Piketty sounded a warning about what a massive problem disparities are several years ago. The social security system is a bulwark against disparity. The modern social security system started in the nineteenth century, so it has a long history.

At the end of the eighteenth century, the economist Thomas Robert Malthus wrote a famous book titled An Essay on the Principle of Population. Later, Keynes praised this first edition, but what was the reason for Malthus writing it? The then British government had decided to raise the benefit level of public assistance and he was arguing how meaningless this was and why they should refrain from it. They wanted to raise the benefit level because there were poor people and they felt sorry for them. But what happens when poor people are given money? The income per person goes up and they might be a bit more affluent in that moment. They will then have more children, so that income per person goes back to the previous level. That is why Malthus called it meaningless.

Even so, Malthus’s time was not that of a full-blown capitalist society, but as capitalism develops, disparities grow. That was when Marx and Engels appeared. The Communist Manifesto came out in 1848. This was an ideology that shook the developed countries in Europe. Yet none of those countries transitioned into socialism but remained capitalistic economies. However, they nonetheless admitted the fact that disparities are a problem that cannot be ignored.

So what to do? The answer that the European countries came up with over a century was the social security system. It is said that the first to introduce a public medical insurance program was Otto von Bismarck of the German Empire. In any case, social security is a bulwark against disparity and that is what Japan introduced it on a full scale after the war. Its necessity is only increasing as the birthrate is declining and the population is aging.

The Problem of the Unsustainable Fiscal Deficit

Let us go back to Japan’s present situation. The key to dealing with the COVID-19 recession all has to do with minimizing disparities.

It goes without saying that the first thing to do is prevent the spread of the disease, but I do not think that is enough. I am going a bit off track now, but I absolutely cannot comprehend the Go to Travel Campaign and the Go to Eat Campaign. Once the disease is under control, people will start traveling and eating out without anyone telling them to do so. It seems pointless to use money for campaigns like this under the current circumstances.

Right now, employment insurance contributions and such are used to keep people from losing their jobs with employment adjustment subsidies so that they are only temporarily granted leave. This is a policy response that cannot be seen in the United States and could be referred to as a Japanese model. I think it is basically correct, but for how long can it be done? It is definitely just a way to buy time. People are granted leave instead of losing their jobs and measures are implemented to stop the disease spread in the meantime. This is a kind of anti-disparity measure.

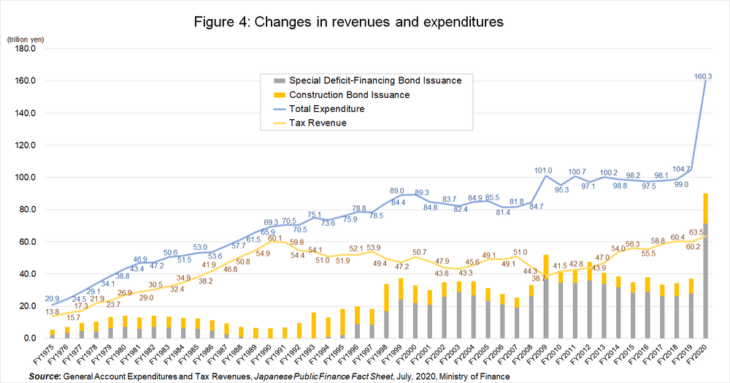

Now, social security currently costs more than 120 trillion yen and premium income is about 70 trillion yen. That means public expenditure is 50 trillion yen, which is running parallel with the fiscal deficit. The fiscal deficit is unsustainable.

The gap between revenues and expenditures is like the widening jaws of a crocodile and in 2020, the crocodile’s mouth has become completely disconnected. The supplementary budget was the issuance of deficit-financing bonds at 90 trillion yen. The cost of social security has only been increasing in government expenditures. This development has been striking especially since the start of the twenty-first century.

The fundamental problem that Japan is grappling with is the declining birthrate and population aging. How do we raise the total fertility rate? Work-style reform might also play a part. It might be necessary to allocate a bit more money to the environment for raising children. Regardless, the growing disparities are a major problem amid the declining birthrate and aging population.

If asked, “Don’t you think it’s a problem?” about the growing disparities, I am certain 99 of 100 will answer that it is a problem indeed. However, it is not a simple problem, but a major one that shakes a healthy society at its core, so it has to be dealt with head-on. A variety of initiatives come to mind, but in terms of state institutions, the social security system is important. Yet it is not financially sustainable. At present, the bill is passed on to the fiscal deficit. In order to drastically resolve this issue, there is a need for fiscal consolidation.

The Basic Policies (for Economic and Fiscal Policy), which summarize basic ideas about public finance, have been customarily made and presented for the last twenty years. When putting together the Basic Policies in June 2020, the first and second supplementary budgets for COVID-19 had already been issued. Normally, how to envision public finance under these circumstances would have been a theme discussed in the 2020 Basic Policies, but it was not touched upon at all. It is very unfortunate.

When I talk like this, I am sometimes told that the current COVID-19 pandemic is a time to hit the gas, so I should not be talking about the brakes. That is incorrect. It is true that it makes no sense to hit the gas and the brakes at the same time, but if you are hitting the gas all you can and are speeding ahead at 180 km/h for some reason, then you also need to give careful thought to how you will engage the brakes further down. If not, it is tremendously dangerous. It is wrong to be preoccupied with the gas alone.

As such, right now when the treasury is gaping wide with the supplementary budgets is the time to debate how we can prepare the way for fiscal consolidation. I really think this is something that ought to have been discussed in the 2020 Basic Policies.

Deflation and Monetary Policy

Let us go back to Abenomics and talk a bit about the themes of deflation and monetary policy. Most emphasized of the “three arrows” of Abenomics was the first “arrow” of monetary easing “of a different dimension.” This had been a major point of contention since the start of the Abe administration. Already during the election in December 2012, the second Abe administration (Abe was still a candidate at the time) started out by criticizing the BoJ and argued that the biggest issue of the Japanese economy was deflation. Thinking that deflation is a monetary phenomenon and that it should stop if there is more money, unprecedentedly aggressive easing commenced under Governor Kuroda Haruhiko in April 2013. They said the monetary base (of the BoJ) would double in two years and that the price stability target of 2% would be achieved.

Economists in academia and think tanks have not been united in how to evaluate this. I am completely opposed to the first arrow of Abenomics. To start with, it is wrong to think that deflation is the biggest issue.

The reason I am saying this is that it has become an axiom in current economics that deflation is a big problem for capitalistic economies, and this comes from the theories of Keynes and the American scholar Irving Fisher that emerged from experience of the Great Depression of the 1930s. However, the deflation back then was one where prices halved in two years.

In Keynes’s Essays in Persuasion, there is a short essay on the issue of deflation. There, Keynes writes that plummeting prices create bad debts and stops the financial system from operating, which stops the capitalistic economy in its tracks. Fisher argued similarly.

What Keynes and Irving Fisher tried to depict as a problem is something that has actually happened to Japan in the past. It is the bubble economy and its bursting. That is, as they argued, the Japanese bubble burst on regular prices and led the Japanese economy to suffer for more than a decade. Japan has already experienced the danger of deflation with regard to asset prices.

However, the deflation that has been a problem since the start of the 2000s has not been about falling asset prices but of regular prices. The drop rate was -1.5% at its worst. Is this kind of deflation a threat against the economy? The answer is no. In fact, the nineteenth century was a century of deflation. In the first half, Britain won the Napoleonic Wars and the British Empire prospered under Queen Victoria. I suspect that the highest average real economic growth rate that Britain ever had was in 1815–1850. They kept growing at an annual rate of 3-4%. In those forty years or so, prices kept falling. In that period, Britain did not see any problem in that at all. The real economy prospered, and the British Empire was at its peak. This is a major counterexample to the proposition that deflation is a big threat to the macroeconomy.

In short, it is wrong to think that a small drop in prices will overturn capitalism. Of course, it would be a terrible problem if prices halved in a year or two. Japan experienced that with asset prices. However, what we are debating in Japan at present is the prices of goods and services. It might have been about -0.3% in the most recent month, but that is not a fundamental problem of the Japanese economy. Of course, it might be better if it were zero. That is because zero means stable prices.

However, a price increase of 2% is considered the golden number all around the world, including by the BoJ. Why is it 2%? If we set zero as the target, then any small hiccup will result in a minus. They said that even deflation of -0.3% is still deflation. In order to keep us completely safe from the minus, we need to set the target for price increase at plus rather than zero. People prefer natural and integral numbers when they discuss things. If so, 0 is followed by 1.

So, would it not be OK to have a price increase of +1%? This is when we encounter the statistical error of the upward bias of the consumer price index (CPI). When compiling the statistics, the CPI actually ends up with inflated figures. In other words, even if it says +1, it might actually be zero. You get a bias of about 1. This is an exceedingly technical discussion. As a result, 1 was added to +1 to get +2, which became the golden number.

Energizing Japan with Innovation

However, it is not so that we have measured how big the upward bias is in the case of Japan. To begin with, is it really such a big issue if it is -0.1? My view is that Japanese prices generally have been stable in the last few years. I see absolutely no reason to strive for a price increase of +2% at any cost.

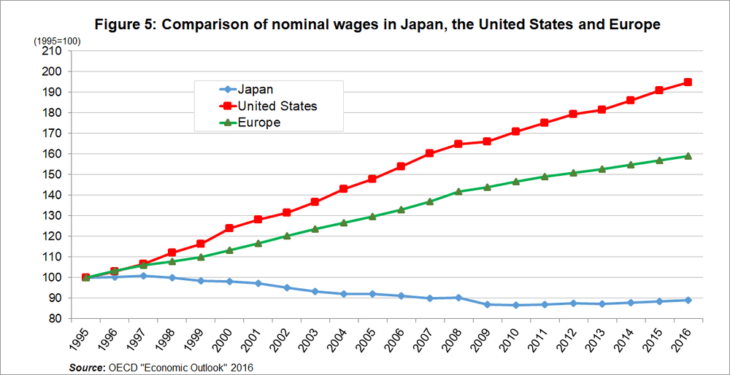

Rather, I think the key to Japan’s deflation is wage deflation. It used to be a deflation stopper that wages do not go down, but this stopper has been removed in Japan so that nominal wages have dropped.

In the Abenomics context, the growth strategy has been economic growth amid a shrinking population, a declining birthrate, and population aging. The third arrow was likely the main prize. The majority perception of the current situation, which exists as an underlying assumption, has been the pessimistic outlook that Japan is done for because the population is shrinking. I also think the shrinking population is a big problem and it gives me a sense of crisis. However, I also want to loudly proclaim that the economies of developed countries do not depend solely on the population.

The German population is also shrinking, and its economy is faltering. But what generates economic growth in developed countries, including Japan and Germany, all comes down to innovation.

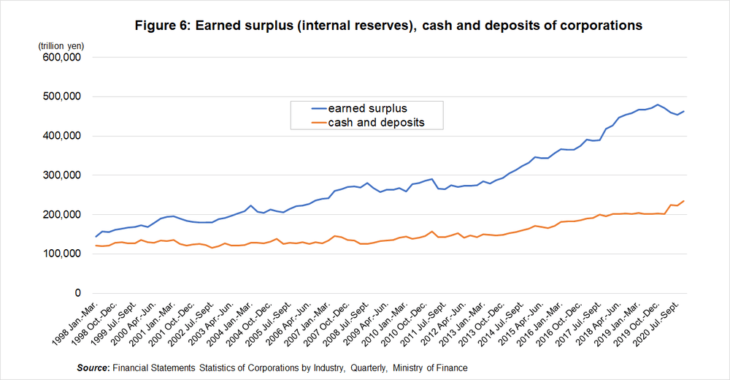

The Japanese government is currently trying to create all kinds of innovation through public and private collaboration in an effort to realize “Society 5.0.” This needs to be done as quickly as possible. Unfortunately, the corporate sector is too dispirited. Normally, private companies in a capitalistic economy will make investments even if they have to borrow funds from the banking sector. Yet looking at the investment-savings balance by field, the corporate sector now has the biggest net savings, outdoing the household sector. The companies’ cash and deposits are piling up. Although this has increased by 75 trillion yen in the seven years of the Abe administration, wages have not gone up. In order to get out of this status quo, I think we first need to energize the Japanese corporate sector.

From the record of a lecture for Gekkan Shihon Shijo held on September 28, 2020.

Translated from “Koenroku: Nihon keizai no genjo to kadai (Lecture: Current Status and Challenges of the Japanese Economy), Gekkan Shihon Shijo, No. 424, pp. 4-13. (Courtesy of Capital Markets Research Institute) [March 2021]

Keywords

- Yoshikawa Hiroshi

- President

- Rissho University

- economy

- COVID-19

- consumption

- Abenomics

- employment

- unemployment

- composite index

- disparities

- social security

- birthrate

- income

- socialism

- capitalism

- Basic Policies

- Economic and Fiscal Policy

- deflation

- monetary policy

- innovation