From Inbound Tourism to Domestic Tourism and Workations—Can Japanese Tourism Recover?

Azuma Toru, Professor, Rikkyo University

The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic

Prof. Azuma Toru

Tourism has been dealt a serious blow by the COVID-19 pandemic. Not only has inbound tourism suddenly decreased since COVID-19 infections started growing last February, travel overseas has shrunk because travelers have nowhere to go. What’s more, even within Japan travel demand for tourism, business travel, and vacation trips to hometowns has greatly decreased.

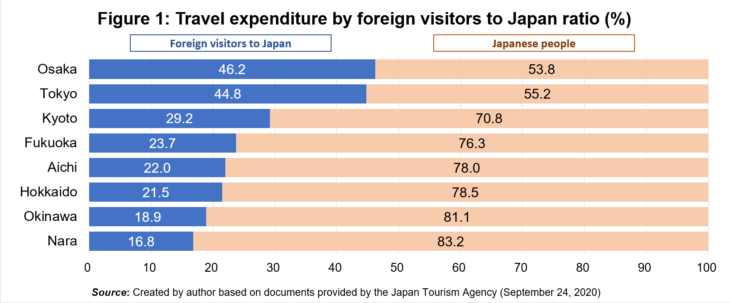

It’s a situation of “lost inbound” in which inbound tourism since last April continues to be down more than 99% month-on-month vs. the previous year. Bearing in mind that the amount spent by inbound travelers in 2019 was 4.8 trillion yen, that has mostly gone and the economic loss is extremely large. In particular, areas with a high ratio of expenditure by inbound tourists, such as Osaka (46.2%) and Tokyo at (44.8%) have been very greatly affected compared to other regions (see figure 1).

This lost inbound effect extends to retail, and the number of overseas tourists visiting department stores has been trending downwards since last February. In April, duty-free revenue was 98.5% down on the same month the previous year and the number of purchasers had similarly dropped 99.5% (Japan Department Stores Association).

The total number of domestic tourists of Japan has also decreased, and is 77.4% down on the previous year during the April to June period (overnight stays 80.9% down and day trips 73.7% down). Expenditure has similarly decreased 83.3% (overnight stays 85.4% down and day trips 76.5% down). (From a Japan Tourism Agency survey into tourism expenditure trends.)

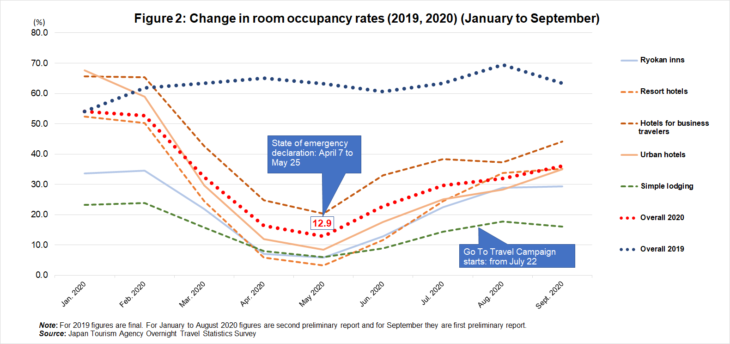

Alongside this lost inbound, domestic tourism demand has also shrunk. Since March accommodation occupancy rates have greatly fallen, dropping to just 12.9% in May (see figure 2). There have been fifty-six bankruptcies in the accommodation sector since February (liabilities of over 10 million yen) (as of 4 pm, 19 November, 2020, according to Tokyo Shoko Research, Ltd.)

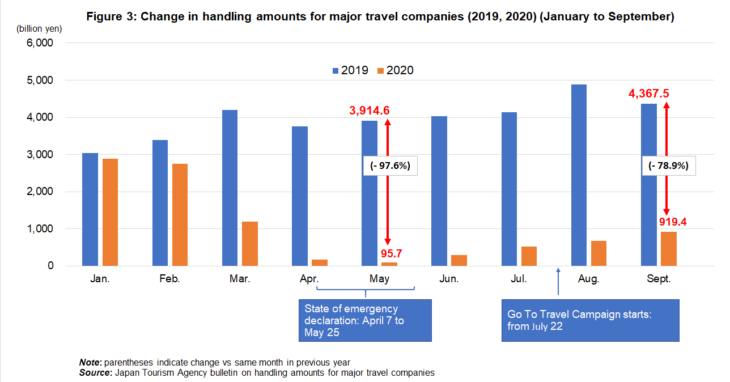

Since last March, the number of transactions for major travel companies has substantially decreased and in May it had fallen by 97.6% compared to the same month the previous year (see figure 3). Since June it has started trending slightly upwards but the situation remains severe. Large travel companies such as JTB have responded to this situation by substantially reducing the number of outlets they operate and have set out plans for a restructuring of the business through digitalization.

The effect of this across-the-board substantial drop in travel demand has extended to the aviation sector. During the first half of the 2020 fiscal year (April to September), passenger numbers on ANA’s international flights were down 96.3% and domestic flights 81.4%. Passenger numbers on JAL’s international flights were down 97.7% and domestic flights 76.1%. Due to this, ANA Holdings has forecast a 510 billion yen net loss for the fiscal year ending March 2021 and announced plans to cut employee pay and reduce its fleet. JAL has also forecast a consolidated net loss of 240 to 270 billion yen for the same period.

From inbound to encouraging domestic demand

In order to revive international tourism, we need the worldwide spread of infection to abate thanks to development and distribution of vaccines and treatments, and for countries to relax their restrictions on entry and exit. Additionally, we need people’s fear of and wariness towards COVID-19 to relax so that they can go on overseas trips without worry and so we can arrange an environment for receiving inbound tourists without resistance. And more than anything we need to revive the passenger flights essential to international tourism.

There are many problems for inbound tourism to Japan too. Even if the government quickly relaxes restrictions on entering and leaving Japan, is it actually good to lift the ban on tourism while Japanese people are still very wary and resistant? Also, can carriers that are struggling to survive again find the energy to run international routes?

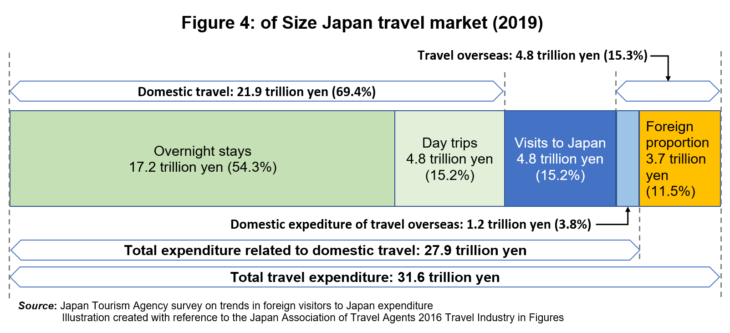

In the absence of prospects for reviving inbound tourism, there’s first a need to encourage domestic demand, and so aim to revive the 21.9 trillion yen domestic travel market (see figure 4).

While infection rates remain high, many people are wary of the infection spread risk that comes from boosting movement of people in large numbers and over large distances, so developing demand for “nearby and local tourism” is an important topic.

Nearby and local tourism doesn’t only encourage local consumption, it’s also an important chance for people to rediscover and reconfirm the attractions of nearby areas, thus nurturing pride and love for local regions. Nearby and local tourism, however, includes many day trips so the amount of money spent is low. A key issue is how to switch from day trips to demand for accommodation. We need to create “reasons for visiting and meaning to stay,” then promote those. For the accommodation sector, working on “close enough to go home that day” nearby and local tourism is the first step toward creating accommodation that’s part of tourism with “accommodation where people want to stay overnight.”

Merits and demerits of the Go To Travel campaign

The Go To Travel campaign was launched on 22 July 2020 as a plan to revive domestic travel demand. It’s not impossible to guess that there was political pressure to prioritize travel over other sectors. However, after Tokyo alone was hastily removed from the plan amid fears of infection spread in the capital, some people had doubts about the seemingly forceful way the plan was introduced. As well as fears that the economic effects would be weakened by leaving out Tokyo, this was a great disappointment to Tokyo companies that were suffering due to the lost inbound. Although Tokyo was added from October and the plan extended to the whole of Japan, as of the beginning of November infections were showing signs of beginning to spread again and there were questions over the campaign’s continuation.

In order to evaluate the Go To policy we need to examine three things: (1) Naturally, we need to look at whether or not the results that were the plan’s main aim were achieved; (2) Whether or not there were problems with the design of the plan and the implementation process; (3) Whether or not feared negative effects or unexpected side effects occurred.

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the Go To campaign was truly a “blessing in a time of need” for tourism-related companies that had suffered severe damage. According to Go To user figures released by the Japan Tourism Agency on 13 November 2020, as of 15 October there had been approximately 31.38 million overnight stays and subsidies had reached approximately 139.7 billion yen. As a result, hotel room occupancy rates recovered to 31.9% in August and 35.6% in September (see figure 2). Travel agents handling amounts also recovered to 86.3% lower than the same month in the previous year for August and 78.9% for September (see figure 3).

On the other hand, problems were also identified. Although overall growth has increased, the benefits have been felt more by relatively expensive accommodation where tourists feel that discounts provide a “bargain stay.” It seems that benefits have been felt less by low priced accommodation where the discounts are smaller and tourists don’t feel they are saving money. In the end, it may be that the support effect of the Go To campaign has worked to the advantage of accommodation with brand power. We can guess that “accommodation worth being picked out by name” or “accommodation that people wanted to stay at one day” captured more demand. In other words, even the policy’s support effects were determined by accommodation’s ability to attract customers.

Since the start of the plan there has been confusion, such as a muddle over cancellation fees, extra allocation to some travel companies outside the budget, accommodation plans with “excessive fees,” non-inclusion of business trip travel, introduction of limits on days stayed, and successive rule changes.[1]

Even though the plan was put in place during the COVID-19 pandemic and hurriedly prioritized, meaning there was insufficient time for checks and preparation, a series of problems arose with the design of the system and the process of its implementation, and the rules changes on each of those occasions have been coldly received. Doubts also remain about its introduction amid a lack of coordination between government and administrative districts.

The most worrisome situation vis-a-vis the Go To campaign is the encouragement of travel demand while infection reduced, and a movement of people that causes infection spread, leading to a prolonged predicament where the reduction of infection is delayed. It may be difficult to investigate whether or not the Go To campaign has led to spread of infection, but it’s not an issue we can ignore. Of course, when this policy was introduced maybe there was a political judgment made to prioritize economic support to tourism-related businesses even if, for example, a slight increase in infection should occur?

As infections start to increase again it is possible to do things such as temporarily stop the campaign or limit it to certain regions. What should we prioritize? Our unsatisfactory politics is worrying. I fear that delayed action will make the situation that much worse.

Issues for the tourism businesses

(1) The accommodation sector: from Go To campaign special demand to attracting customers self-sustainingly

At most the Go To campaign provides temporary special demand and is only to tide companies over. Some also worry about a rebound due to “bringing forward” demand. In any case, whether or not continuing demand can be secured will become a big issue after the campaign concludes. Going forwards there will be a focus on whether tourists’ experience of staying in higher quality than usual accommodation will cause demand for an overall “upgrade” and whether accommodations can secure new customers who want to stay with them even without discounts.

Special demand spurred by a sense of getting a bargain will disappear with the end of the Go To campaign. As we approach “independence” stage following the Go To campaign’s conclusion, accommodations without their own ability to attract customers may be eliminated. Whether inbound or domestic tourism, companies that rely on tours from travel agents will not be chosen as accommodation in the era of personal travel and the internet. A time will come when “self-sustaining efforts to attract customers” are necessary for “tourism demand by spontaneous actions (with or without campaigns).” When that happens, and when the Go To campaign finishes, the true attractions of accommodations will be tested. Are they worth being picked out by name? Is there a reason to visit them? Can they become accommodations worth staying at?

An accommodation’s attractions aren’t limited to gorgeous food and sophisticated hospitality. They need such things as an “at-home” atmosphere and interaction between staff and guests. Accommodations that are worth specially choosing need to assert their uniqueness and separate themselves out by tapping their distinct characteristics amid diverse accommodation needs.

What’s more, a future issue may be how to meet increased new demand prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, such as for workations[2] and satellite offices.

(2) Aviation sector: are LCC the key to restructuring the business?

While the outlook for global demand is uncertain, airline companies that are suffering due to fallen demand during the COVID-19 pandemic have to first build on recovered demand for domestic routes and income from air cargo, and from there recover the strength needed to run international routes. But if business demand continues to fall due to online meetings etc. becoming established, that may affect the recovery of income from domestic routes. Unlike business demand, tourism demand is relatively easily affected by price and tends to be unstable depending on the day of the week and changing seasons. If airlines become more reliant on this there is a possibility that price levels may fall. If recovery of income from domestic routes is delayed it will affect the recovery of international routes, and could cast a dark shadow on inbound tourism recovery.

In this situation, ANA Holdings has announced plans to launch a medium-haul LCC (low-cost carrier) “third brand” alongside ANA and Peach. There are questions about how this third brand will avoid cannibalization within the group not just regarding price points, but also customer segments, routes and services. And as well as separating itself within the group, how will it come up with a USP (Unique Selling Proposition) to differentiate itself from competitor companies? JAL has also indicated a policy of aiming to capture tourism demand in the future, but also at the same time actively use LCCs since it is difficult to be profitable as an FSC (Full Service Carrier). It has already set up a subsidiary ZIPAIR and is starting medium-haul LCC flights.

Going forwards, there is a possibility of diverse options (business categories) for airline services, customer types, uses and price lining.

Possibilities brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic hasn’t just brought us face to face with a tourism industry struggling in a slump. It may have given us an opportunity to visualize tourism in the near future.

By being forced to telework, we have pictured a new post COVID-19 work style and perhaps imagined a way of life with free choice over work style and breaks, time and place. As long as the necessary ICT (information communication technology) environment is in place, we could work comfortably in a rich natural environment and refresh ourselves as needed.

This kind of new work style that fuses work and vacation is called “workation.” This style of work and vacation might also be viewed negatively, with criticisms such as, “There is no clear distinction between work time and off time,” or “You can’t enjoy holiday destinations if you bring your work.” But as teleworking continues, many people have realized that more work can be done without going to the office than they thought, and that what they can do at home they can also do at a resort. Ironically, COVID-19 may have provided the tourism industry with new business opportunities. For local regions it is attracting attention as an opportunity for new interaction and getting new people involved, and accommodation providers are starting to address demand for workations.

Amid the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, information, communications and technology have created another potential and that is “connecting with local areas and enjoying their benefits, even without travel.” Some people have had the experience of connecting with local areas online and enjoying local products delivered to them. Meanwhile, some people might imagine a time when we can enjoy VR (virtual reality) tourism. Rather than focusing on what VR lacks, many people talk about how VR could actually encourage people to want to go to places. VR can function as promotion; that is, what it lacks makes people want to visit more. Yet eventually, if this technology progresses, the day may come when VR creates links with local areas and provides enjoyment… and we may call this “tourism.” And for those who cannot easily travel, it may provide a chance to enjoy “tourism for all.”

What kind of tourism will emerge with changes in people’s lifestyle and advances in technology? We may have unexpectedly caught a glimpse of that during this COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

COVID-19 has produced—and may yet produce—various different changes. Here, I’d like to highlight three.

(1) It has brought opportunities to newly discover the “highlights” of local areas though short-distance travel to close-by areas rather than long-distance trips.

(2) Due to the establishment of telework, a shift in work styles, and other factors, demand for business travel has shrunk. Thus, we can expect accommodation and transport companies’ reliance on tourism to increase. Also, “workation” trips to local areas are less restricted than standard long breaks and in some cases may lead to demand for frequent visits to local areas. In contrast to tourism to date, there’s a possibility this might lead to a new style of travel in which people “enjoy daily life in local areas.”

(3) Interest in new tourism that uses VR, AR (augmented reality) and MR (mixed reality) We’ve entered an age when video games are called sport, and it is an open question as to whether VR or others can be called tourism or not. But it is very possible that advances in technology could create new ways to enjoy local areas. It’s not known whether this could replace the tourism we have now, but when it does become reality, to what extent will the tourism industry be able to stay looking like it does now? The effects of COVID-19 are truly enormous, and that’s not limited to enormous damage; they are accelerating change too. Where will tourism go next? The hope is that, instead of tourism that is uniform and aims to increase numbers, diverse ways to enjoy tourism that meet diverse needs will be created. Each of those trips could lead to precious memories and also to tourism that features high-value experiences that turn visitors to local areas from guests into fans. But we mustn’t forgot that what enables that is not technology but the human element. We can expect the post COVID-19 era to demand QOT (quality of tourism).

(Written on November 20, 2020)

Translated from “Inbaundo kara Kokunai-kanko, wakeishon—Nihon no Kanko wa Tachinaoreruka (From Inbound Tourism to Domestic Tourism and Workations—Can Japanese Tourism Recover?),” Chuokoron, January 2021, pp. 136-143. (Courtesy of Chuo Koron Shinsha) [March 2021]

[1] Other problems with the Go To campaign that have been noted include the illegal acquisition of shared regional coupons, issues with per day fees paid to those seconded to the managing office, delayed payment of discount monies to travel companies, and unfair distribution of information among travel companies. Others have also pointed out “distrust and dissatisfaction towards the government” on the part of travel companies and “a deepening gulf with the travel industry” (Yamada Shizuka), as well as “distrust from society” towards the travel industry and “internal division” within the industry (Kanda Tatsuya). (November 9, 2020 edition of Shukan Travel Journal)

[2] In order for workations to become popular the following is required: (1) Creation of opportunities for individuals to freely choose; (2) For companies to provide options for facilities and programs; (3) Systematic implementation within companies, such as clearing related labor management issues. In local areas too, it is necessary to create attractive features for users, such as environments where it’s easy to work and feel refreshed, provision of comfortable daily life during the stay, and the offering of opportunities to interact with local people.

Keywords

- Azuma Toru

- Rikkyo University

- Institute of Tourism

- COVID-19

- tourism

- lost inbound

- aviation sector

- Go To Travel

- Japan Tourism Agency

- domestic tourism

- nearby and local tourism

- accommodation sector

- workation

- VR tourism

- QOT

- quality of tourism