What to Do with the Public Finances: Revising the Budget Compilation to an Ad Hoc Approach

Iwamoto Yasushi, Professor, University of Tokyo

Key points

- Correct inconsistencies between targets and predictions for better fiscal soundness

- Difficulties to compile budget by end of 2021 as planned

- Initial budget reduction followed by revisions every quarter

Prof. Iwamoto Yasushi

The Emergency Economic Measures for Response to COVID-19, which was formulated in April, includes two stages: an “Emergency Support Phase” until the COVID-19 situation is resolved and a “V-shaped Recovery Phase” after it has been resolved. Supplementary budgets of unprecedented scale was put together to realize this, so much that the state’s general account expenditure included large-scale public spending corresponding to about 1.5 times the FY2019 figures.

The “Basic Policy on Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform 2020,” created in preparation for the FY2021 budget compilation, and the “Economic and Fiscal Projections for Medium to Long Term Analysis,” which showed economic and public finance projections until FY2029, were compiled in July. With the future uncertain, let us think about implications of making projections and how to manage public finances.

One goal of preparing medium-term economic and fiscal projections is to ensure that the policy structure consistent. Since the Basic Policy assumes that the Tokyo Olympic Games will take place in 2021, the COVID-19 epidemic should be contained by then, and it is contradictory that the budget includes measures against infectious spread in FY2021.

Moreover, the goal for fiscal consolidation is to achieve a surplus in primary balance of national and regional governments combined by FY2025. Even if we assume that it will take time for the economy to recover after the pandemic has ended, there is little reason to be pessimistic about the economy in 2025. If we can deal with the decrease in corporate tax from loss carried forward, it is thought that the impact on the primary balance for that period can be more or less neutralized.

If public finances cannot overcome the COVID-19 shock, then it is not very likely that the Basic Policy can realize an economy that has overcome COVID-19. There is no reason for changing the period when to achieve the primary balance surplus. This makes it suspicious that the Basic Policy has lost all references to the targets of fiscal consolidation that have been promoted for some time, such as achieving the primary balance surplus 0f national and local governments combined by FY2025 and stably lowering the debt-to-GDP ratio.

The second goal for making medium-term projections is to present a picture of stable fiscal management in the medium term, thereby avoiding short-sighted policy decision-making and maintaining fiscal discipline. However, fiscal discipline has been lacking for some time and this has only sped up with the COVID-19 response being used as an excuse.

The medium-term estimates from January 2018 delayed the prospect of achieving a surplus to FY2017 despite an optimistic scenario for economic growth, thereby shelving any attempt at integrating the target to move the primary balance surplus by FY2025. The new estimates have delayed that period by another two years. It is problematic that the inconsistencies between targets and projections for fiscal consolidation have grown even bigger.

It is also inappropriate that matters of financial resources were not discussed when formulating the measures. In the case of the restoration projects after the Great East Japan Earthquake, which required big temporary expenditures just like the COVID-19 measures, the financial resources for the restoration were secured by as a way to absorb the negative shock by spreading it out into the future (tax smoothing). It would make sense to seek to cover the temporary public expenditures for COVID-19 by a similar tax smoothing approach, but this did not happen.

If we take a pessimistic view on the spread of COVID-19, then it is very unlikely that the targets for achieving the primary balance surplus can be maintained. Additionally, it is difficult right now to accurately predict how long the pandemic will continue, how much it will weaken economic activity, and to what extent fiscal measures will be necessary. If economic activity continues to contract, then more public spending will be needed and the government net deficit will worsen more than expected in the medium-term estimates that anticipate an early end to the COVID-19 pandemic.

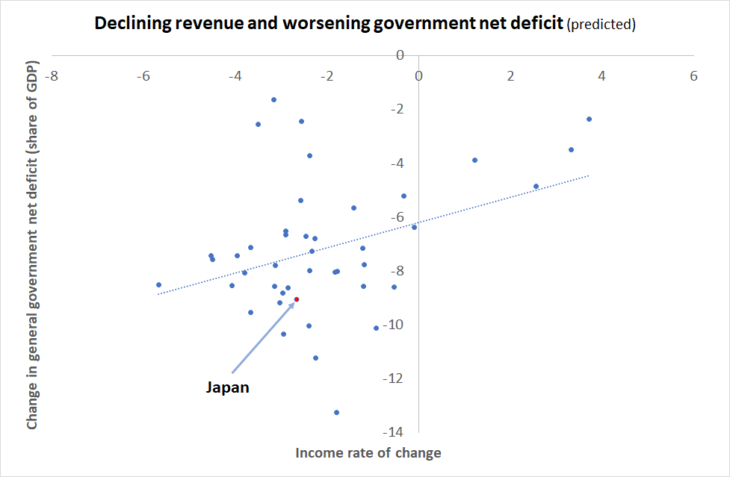

Based on OECD data, looking at different countries’ responses in a scenario of no second wave, the tendency is for the government net deficit to be worse the bigger the decrease in GDP (see figure). Even though the impact of the first wave was relatively small in Japan, the government net deficit has worsened a bit more than the trend line. The pressure on public finances might be bigger here than in other countries in case of a second wave. It is also thought that Japan, where infection cases were few in the first wave, will have more infections than other countries during a second wave, which will increase the risk of high pressure on the public finances.

Note: The x-axis shows the real GDP rate of change from Q4 2019 to Q4 2020; the y-axis shows change in general government net deficit (share of GDP) from 2019 to 2020

Source: Created based on the Economic Outlook, OECD by the author

What does this mean for how we think about the third and later supplementary budgets to be formulated as well as budget compilations in FY2021 and beyond? There is a wide range of possibilities for policies that may have to change due to COVID-19, so it is extremely difficult to devise appropriate policies in a situation that keeps changing from day to day and hour to hour. The ideal approach would be to come up with alternative policy plans like “Plan B” and “Plan C” that anticipate a wide range of scenarios outside of the main scenario, so that we can choose from those plans when the circumstances become clearer and keep altering them when they do not match the actual conditions.

However, such ideas are difficult to harmonize with the budget compilation process, which has the National Diet deliberate and decide on expenditures in advance. An exceptional measure has been taken for the FY2021 budget compilation as the deadline for the request for budgetary appropriations was postponed from end of August to end of September. Even so, it is unlikely that it will be possible to compile a budget that precisely accommodates the circumstances until the end of FY2021 by then.

If a decision can be made rationally, it can be made once and then changed later if it does not suits the circumstances. The budget authorizes government spending, so it is not allowed to make expenditures not in the budget, but it is allowed to not make budgeted expenditures. For example, in the case of projects planned for the post-COVID-19 period, it will not be a violation of the Public Finance Act even if they are postponed due to the pandemic not subsiding. However, projects that benefit interest groups, once budgeted, may resist being foregone and are executed as if even if the circumstances change.

Taking into consideration the losses incurred by irreversible expenditures that cannot be changed later because they cannot be revised when the circumstances change, the value generated by postponing decision-making is formularized in the concept of “real options,” and the calculations of such value is also practical in financial engineering.

If this way of thinking is applied to the budget compilation, then it should be possible to decide from the beginning to move policies affected by COVID-19 to supplementary budgets without including them in the initial budget. This is exceptional for national budgets, but it is commonly used by local governments. If an election is coming up after the compilation of the initial budget, a “skeleton budget” is compiled that includes only minimal expenses and leaves most policy expenses to be compiled under the new leader.

On the national level, a provisional budget is compiled if the initial budget cannot be put together by the start of the fiscal year, but this differs from a skeleton budget since it is assumed that a full initial budget will soon be approved.

It would not be practical for the FY2021 initial budget to put a “minus ceiling” on it by evenly lowering the budget request compared to the previous fiscal year, but it would be no problem for the initial budget to be considerably reduced compared to FY2020 as a result of calculating the budget based on COVID-19’s effect on each policy. It would then be possible to put together a supplementary budget each quarter.

Japan has no culture of devising policies as “Plan B,” but now it is essential. We should take this corona crisis as an opportunity to improve the quality of policy formulation and budget compilation.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on 13 August 2020 under the title, “Zaisei wo dosurunoka (II): Yosanhensei minaoshi, rinkiohen ni (What to Do with the Public Finances (II): Revising the Budget Compilation to an Ad Hoc Approach).” The Nikkei, 13 August 2020. (Courtesy of the author)

Keywords

- Iwamoto Yasushi

- University of Tokyo

- public finances

- fiscal soundness

- budget

- Emergency Economic Measures for Response to COVID-19

- COVID-19

- V-shaped recovery

- supplementary budgets

- Basic Policy on Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform 2020

- Economic and Fiscal Projections for Medium to Long Term Analysis

- Public Finance Act

- predictions

- Plan B