New Phase of International Trade Policy III: No conflict with RCEP, TPP

Oba Mie, Professor, Kanagawa University

Key points

- Needs to center around formulation of shared rules for investment, intellectual property

- Important that China accepts restrictive provisions

- Needs to have shared rules aimed at sustainable development

Prof. Oba Mie

In November 2020, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) was signed by 15 countries, comprising the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) as well as Japan, China, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand. This created a huge economic zone that accounts for around 30% of the world’s GDP, trade and population.

The start of negotiations by 16 countries, including India, was announced in November 2012. Aligning the complicated interests of each country was not easy, and the deadline for negotiations was postponed many times. After many twists and turns, a negotiated agreement was reached. India ultimately decided not to join.

Through the 2010s, the future of the regional order in Asia has become increasingly uncertain in a changing regional environment due to the shifting balance of power between the United States and China, as well as the trend toward global protectionism as exemplified by the confrontational international trade policy of the Trump administration. The negotiated RCEP agreement expresses the country risk hedge in response to this unstable situation, as well as demonstrating the stance of the East Asian nations to maintain and further develop the free and open international economic order that is currently being shaken.

In terms of what the RCEP has accomplished, the tendency has been to focus attention on the phased elimination of tariffs on trade in goods. However, even more important for future regional integration and international economic order is the fact that the RCEP has succeeded to some degree in creating shared rules to accelerate economic development by promoting a 21st century free trade agreement driven by the development of cross-border supply chains.

East Asia has achieved development through the expansion and deepening of cross-border supply chains. To develop further, international rules will be necessary to ensure a smoother two-way flow of goods, people, ideas and investment than ever before. The successful conclusion of the RCEP negotiations was due to a certain degree of shared awareness of these issues on the part of the authorities of the RCEP participating countries.

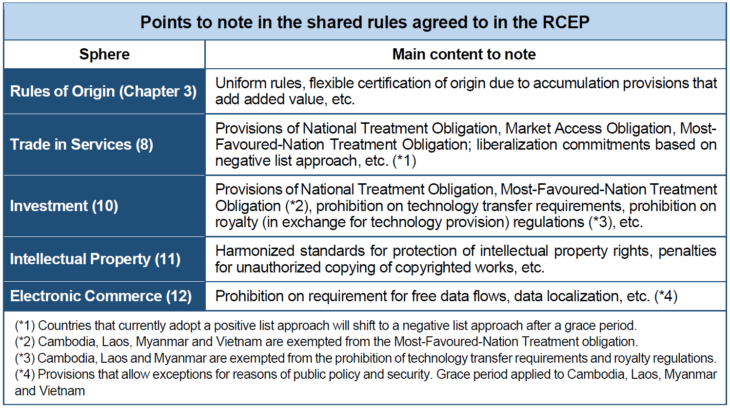

Therefore, the core of RCEP is the formulation of shared rules, which will have a more dynamic effect than the elimination of tariffs. In particular, it should be noted that the provisions in the chapters on rules of origin, services, investment and intellectual property rights have been established at a level higher than those in the existing ASEAN+1 free trade agreements (FTAs), the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMs), and the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) (see table).

In addition, the Electronic Commerce Chapter (Chapter 12) includes provisions on the prohibition of data localization, which requires the installation of local servers, and on data free flows, which does not prevent the cross-border flow of electronic information, on condition that it does not prevent restrictions being imposed for reasons of public policy or security. Given the expansion of the digital economy and the expected acceleration of digital transformation (DX), the establishment of these provisions is significant.

The 15 countries differed significantly in terms of economic scale and level of development, and various conflicts of interest came to light during the negotiation process. Consideration also needed to be given to the transition period for countries to comply with the agreement. Further, the degree of liberalization and standard of rules for trade in goods are lower than that of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP, TPP11), which entered into force without the United States in December 2018.

Nevertheless, the fact that the diverse countries of East Asia have achieved certain shared international rules pertaining to economic activity will significantly define the future regional economic order. The RCEP establishes provisions for holding joint committees and establishing secretariats, and more institutionalization is expected in the future.

Given that the RCEP has established rules that restrict China in terms of investments and Electronic Commerce, the view of the partnership as a China-led framework is overly simplistic. Rather, more attention should be paid to the fact that the RCEP aims for region-wide economic integration based on ASEAN Centrality, which is based on the ASEAN + 1 FTAs that ASEAN has formed with countries outside the region through the 2000s.

Previously, ASEAN set a direction for development by bolstering the connectivity of Southeast and East Asia as a whole, including the reinforcement of supply chains. Its importance has been further accentuated as a measure for the recovery and development of economies hit by COVID-19. Of crucial importance is the fact that RCEP is the first Regional Trade Agreement (RTA) to include China, South Korea and Japan, and that it came into existence for the first time on the sidelines of ASEAN.

To speak of the TPP and RCEP in terms of conflict is to misread the nature of region-wide economic integration. The RCEP and the TPP have shared aims: to challenge protectionist tendencies, to maintain and strengthen a free and open international economic order, and to deepen and expand supply chains. In the future, the TPP and RCEP may form the basis for the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP), which aims to achieve the integration of the entire Asia-Pacific region.

The RCEP is certainly not immune to geopolitical rivalry in terms of which country will be the central player in regional economic integration. With the presence of the Chinese economy increasingly driven by the Belt and Road Initiative, the trend toward expansion of trade between China and ASEAN and investment from China continues.

The fact that China has participated in the formulation of rules that are not necessarily positive for its economy in the short term and that regulate its economic activities in defined ways is significant. A China that seeks to develop while asserting compliance with rules of international order is more formidable than a China that acts outside the framework of a free and open economic order. President Xi Jinping referred to the possibility of China joining the TPP. His true intention is still not clear. However, it might indicate future moves by China to strengthen its compliance with international rules in order to develop its own economy as well as to expand its influence in the regional economic order.

Assuming that the expansion of China’s economic presence is inevitable, Japan and other RCEP members should aim for the development of the entire region by further encouraging its participation in the supply chains of the economic entities of all countries, including ASEAN’s least developed countries.

In terms of balancing the presence of the expanding Chinese economy, the expected accession of India is understandable. However, India’s participation will be contingent on the determination of Indian authorities to eliminate protectionism and remove various local regulations, espousing a shared vision that increasing access to cross-border supply chains is the best option to promote its development.

The expansion of supply chains across national borders driven by market mechanisms will create disparities between those economic entities and regions that are able to participate and those that are not, as well as potentially causing damage to the environment and other public interests. To address these challenges, it is essential that the RCEP establish shared rules to achieve equitable and sustainable development.

The Small and Medium Enterprises Chapter of the RCEP demonstrates the partnership’s awareness of these issues. However, unlike the TPP, the RCEP does not include a labor and environment chapter. Japan should endeavor to further enhance the content of the RCEP by adding new provisions for equitable and sustainable development.

Translated by The Japan Journal, Ltd. The article first appeared in the “Keizai kyoshitsu” column of The Nikkei newspaper on January 21, 2021 under the title, “Shin-kyokumen no Tsusho-seisaku (III): RCEP, TPP to tairitsu sezu (New Phase of International Trade Policy III: No conflict with RCEP, TPP).” The Nikkei, January 21, 2021. (Courtesy of the author).

Keywords

- Oba Mie

- Kanagawa University

- international trade policy

- Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership

- RCEP

- TPP

- investment

- intellectual property

- China

- ASEAN

- supply chains

- data free flows

- digital economy

- digital transformation

- DX

- shared rules

- equitable development